I believe that authenticity matters; hiding who we are stifles growth opportunities for the individual and collective. So in this blog I write about all things that genuinely fascinate me: art, spirituality, the puzzles of personhood--and their ongoing interplay. For some, learning the artist's thoughts contaminates the experience of the art, and I respect that. It might be best to avoid this blog and visit only my gallery pages. Personally I can't get enough of the stories, ideas, and people behind art, so this blog is most appropriate for an audience similarly curious and open-minded, and who won't take offense at challenging perspectives and taboo topics. It's especially for those who are aware they're undergoing a spiritual awakening and seek to feel less alone in that process. I wouldn't be at this better place in my life if it weren't for the wayshowers I found online who helped me understand what was happening to me and to the world, and I hope to pay it forward by doing the same for others on the awakening path.

|

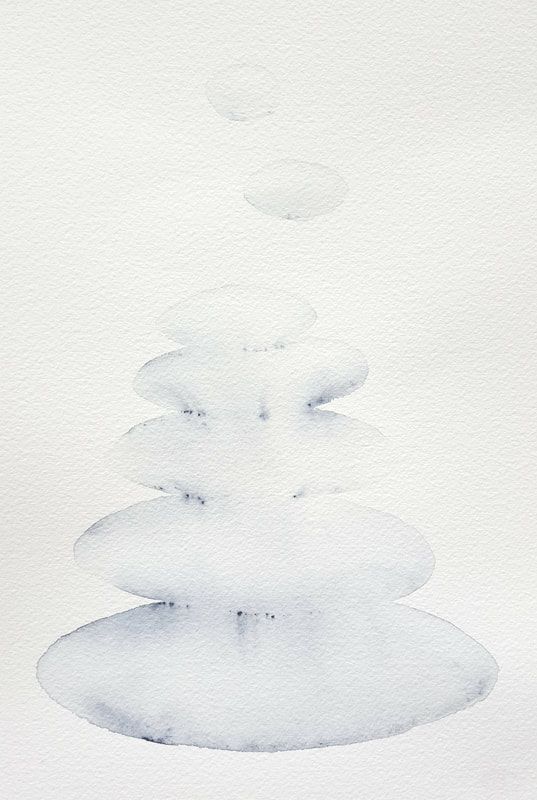

'Grok' means to understand so thoroughly that the observer becomes a part of the observed. - Robert A. Heinlein, Stranger in a Strange Land I started painting cairns in 2014 and I didn't know why. It just seemed like a nice thing to paint. Kind of new-agey, a little Zen. Starting with very stylized stone shapes in pale stone colors. One stacked on top of the other in a fairly uninteresting, uniformly tapering arrangement. Later I added space between two or three stones at the top as if they were levitating. For no particular (conscious) reason, just to add some interest. Eventually I found out about an irresistible line of paints made of pulverized crystals and gemstones, like amethyst, garnet, and turquoise, and rocks that come from places with mystical connections, like a gold-brown iron oxide from Arizona named after the Yavapai tribe and the red sandstone from the new-age mecca of Sedona. What if I painted rocks, with rocks? After some experimentation with these new paints I allowed the pigments of the painted stones to run together and flow down the stack, using slope and gravity and a lot more water than I did before. This seemed like something important to do and I liked the effect. Actually, it seemed like the process was maybe more meaningful to me than the effect it produced. It became my favorite approach to cairns. I start with the paper flat on the work surface and load a big brush with plain water to create puddles on the paper in stacked stone shapes, forming the watery silhouette of a cairn. Then I fill a brush with full-strength paint and drop this darkest pigment into the areas of the cairn where shadows would naturally fall, definitely between stones and maybe to the left or right sides of the cairn, depending on the imagined light source. Something mesmerizing happens in this early step: each paint reveals its unique character as it reacts to contact with the water. The finer the pigment, the more the paint appears to bloom in the water as its particles race out over the surface tension. The paint dries in wispy patterns if left alone at this point, like the cairn above painted with Sedona sandstone. The next step is my favorite: I incline the paper so that the water in the puddles runs down through the cairn shape, and I'll strategically send more water streaming from my brush--occasionally by applying direct friction with the bristles to erode existing pigment, but usually by allowing the water to drip from the over-saturated brush and find its own way through the paint. The water picks up concentrated color from the shadow areas and redeposits it further down the painting in sedimentary trails. This erosive process also causes the darkly pigmented areas to break up and their edges to soften, forming rounded shapes that look like tiny river stones--much in the way a rushing stream smooths and polishes the rocks it contains it over time. There's a spiraling self-referential theme to these cairns: paintings of stones using a technique that reproduces the process that creates stones, using paint made from the stones depicted. I call this painting style sculptural flow. There are so many variables that influence the cairn paintings: brand and thickness of paper, amount of water used, concentration of paint, source of the pigment, ambient temperature and humidity, length of time I wait between stages of the painting, my own mood and reserves of patience I bring to the experience. Although I start with some idea of how I'd like the finished cairn to look, my process ensures that I can't really predict or completely control the outcome--and that's how I want it. After years of experimenting with watercolor painting styles, I routinely found that the more I controlled the paint and water, the less I liked the result because it looked dull. Watercolor ended up almost indistinguishable from colored pencil. What's the point of using a medium if it fails to showcase its unique attributes or mimics an entirely different medium? When I view all the elements (water, paint, slope, gravity, time) that can join the painting process as co-creators with me, able to express themselves in their signature ways without my complete control, there's a lively quality to the finished work. I want to see evidence of them doing what they naturally do when given freedom. For example, water splashes and runs, carries and deposits sediment, and forms that thin mineral edge at its boundary, like dried raindrops on a windshield. Paint exhibits an incredibly wide range of values from crazy dark straight from the tube to pastel pale, depending on how much water it gets to play with. Time makes its mark when I wait long enough so that certain areas of the painting lose their moisture, producing different effects as water runs over dry patches in concentrated drips instead of fanning out over still-damp paper. This painting style serves as an exercise in co-creation and surrender--two things that I've also adopted in my approach to life in general ever since rediscovering painting several years ago. That approach led me to a life full of surprising discoveries and my cairn paintings have come along for the adventure--in some sense, leading the way. They reflect my love of the the southwestern region of the United States, which I fell for after housesitting in Tucson in 2014. I couldn't get enough of the desert so I moved to Albuquerque in New Mexico the following year. A new neighbor there pointed out to me the phenomenon of virga that's very common in the skies out west: rain falling but evaporating before it hits the ground. In the distance it seems to form curtains in the sky. I realized that the cairns I had been painting months before then, using the color known as Payne's gray, seemed to depict (or predict?) the virga I'd see over moody landscapes. I began more consciously painting cairns to create atmospheric landscapes within them--and, as usual, my materials seemed to join eagerly in conscious collaboration. Something interesting happens at the bottom of a watercolor painting as it dries on an incline: the collected water blooms upward through capillary action in drying paint, automatically forming ghostly foliage shapes ideal for landscapes. Without need for a brush to create every branch. Ever since 2014 my painting practice has been punctuated with road trips and long hikes for inspiration and, more importantly, because I have lots of catching up to do with nature after spending years holed up in office cubicles. I've made a point of exploring the national parks and ancestral pueblo ruins sites in the Four Corners states, such as Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, Sedona's rock formations in Arizona, Canyonlands in Utah, and Mesa Verde in Colorado. Everywhere I went I saw cairns along the trails, marking the way. I ended up painting cairns of all kinds, made from rounded river stones to more angular sandstone slabs. At first I thew away more paintings than I kept, but eventually I grew more satisfied with the results and comfortable with the process. Often when I'm painting a different subject and end up frustrated I'll paint a cairn--and it will center me again. I walked right into that metaphor (pun intended), didn't I: what are cairns when we come upon them in the real world as we're crossing a stream or climbing a rock formation, but comforting sights that tell us, this is the way? That's what my two-dimensional cairns are for me as an artist: they reassure and bring me back to my path. The cairn is my signature subject and--or because--it's my meditation, my personal version of the Zen Buddhist practice of brushing the ensō. The ensō is a circle completed in one or two strokes of a brush dipped in ink. It's a paradoxical exercise in discipline and co-creation, intention and surrender. The artist's goal is a circle, but given the ground rules of the practice, any perfection aimed for can lie only in the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, which celebrates the perfection of imperfection. The telltale human touch of a hand-drawn shape and evidence of materials used, like stray brush hairs trailing ink at the circle's ragged edges, are what gives each ensō its unique beauty and value. Brushing the ensō represents a co-creative journey--and so does painting the cairn. As usual with everything art and life, my cairn paintings are evolving. See the next blog post, Grokking the Cairn, Part II. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

May 2022

Categories |