I believe that authenticity matters; hiding who we are stifles growth opportunities for the individual and collective. So in this blog I write about all things that genuinely fascinate me: art, spirituality, the puzzles of personhood--and their ongoing interplay. For some, learning the artist's thoughts contaminates the experience of the art, and I respect that. It might be best to avoid this blog and visit only my gallery pages. Personally I can't get enough of the stories, ideas, and people behind art, so this blog is most appropriate for an audience similarly curious and open-minded, and who won't take offense at challenging perspectives and taboo topics. It's especially for those who are aware they're undergoing a spiritual awakening and seek to feel less alone in that process. I wouldn't be at this better place in my life if it weren't for the wayshowers I found online who helped me understand what was happening to me and to the world, and I hope to pay it forward by doing the same for others on the awakening path.

|

This is the fourth in a series of posts on what I've learned from my dysfunctional upbringing and my thoughts on how the systems and beliefs that comprise our culture can improve. For my full story, see the December 2020 post titled, "We Are Shaped by Our Experiences: An Origin Story Pulled from the Shadows." My intention is to inspire others to develop greater awareness about their own lives and to share ideas for building healthier, more supportive families and communities. Because I believe, as Teal Swan says, "We are given the very wounds we are meant to teach others to heal."

"The Buddha said at some point...with our thoughts we create the world that we live in. But what he didn't say, which is really the insight of modern psychology, is that before 'with our thoughts and our minds we create the world,' the world creates our mind." - Dr. Gabor Maté

Let bygones be bygones is the common, shaming message surrounding childhood trauma ordered by people who never experienced nor studied it, or who themselves are in deep denial about their own history. Yet something in me that knew that the keys to really understanding myself and what I needed to heal--and help prevent from happening to others--lay buried in the past that increasingly preoccupied my mind. It turns out I was on to something. Because science now bears out that a person’s earliest experiences in life have the greatest impact on their physical, mental, and emotional development and well-being due to physiological factors unique to the very young.

Image credit: Jennifer Thangavelu, based on a reference photo by Joebaby Noonan. My painting of a young wild dolphin I swam with off the coast of Bimini in the Bahamas (based on a photo taken when he was even younger, before I met him). His dorsal fin was chopped, likely by a shark--but dolphin pods (communities) are incredibly supportive, enabling members to recover easily from trauma. He's very charismatic today. Joebaby named him Romeo.

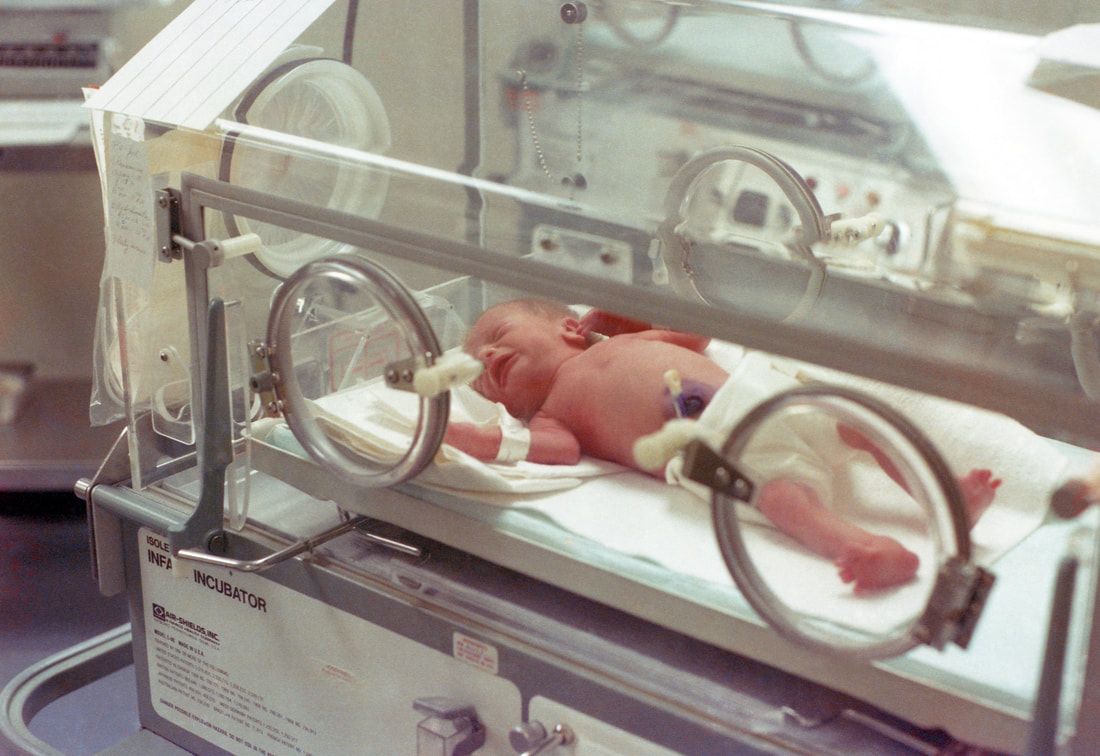

Prenatal Maternal Stress: The Earliest Source of Trauma In their 2012 book, Scared Sick: The Role of Childhood Trauma in Adult Disease, authors Robin Carr-Morse and Meredith Wiley detail how developmental trauma can start even before a child is born--and it’s not just about quality and quantity of nutrients crossing the umbilical cord: “Inadvertently shared within the very first relationship, a mother’s emotional stress during pregnancy by itself may take a greater toll on her baby than on her own body.” The authors of Scared Sick explain: “The brain’s most essential role is to ensure survival. So if, through sensual perceptions or chemical messages, the fetal or newborn brain chronically detects that the world is aggressive and hostile or that survival depends on vigilance, his or her very plastic brain will shape itself accordingly, sending chemical messages to the endocrine and immune systems to prepare to survive in such a world.” This brain adaptation can provide an evolutionary advantage in animals that must survive in a hostile environment. But in the human world, where we typically don’t face life-or-death circumstances on a daily basis, a person whose nervous system was programmed for heightened threat detection fares badly, both socially and in terms of their ability to live a productive, fulfilling life. Daily tasks of modern life require the ability to focus for long periods of time, discern, connect with people in a healthy way and make decisions in the short- and long-term best interests of the self and others--abilities that properly develop only when the individual’s upbringing has been free of chronic, undue stress. Karr-Morse and Wiley warn: “[T]he emerging science is forcing us to acknowledge what ancient wisdom has taught, and what many of us have intuitively known: maternal stress affects the fetus. Maternal stress during pregnancy is highly correlated with spontaneous abortion, preeclampsia, preterm birth, low birth weight and the adult diseases that follow these conditions." Arguably I had been June’s most stressful pregnancy, given that during it she already had the additional work of caring for my older sister and hadn’t yet hired Mrs. Moss, the woman who would help out only after I was born, and who would be there throughout and well after June’s entire pregnancy with Sia, my younger sister. Sia benefited tremendously from Mrs. Moss's presence: not only was June less stressed, but Mrs. Moss clearly favored Sia over Jillian and me and gave her more attention. Every child needs an adult on their side, making them feel special and loved. Sia was fortunate to have that (among other advantages, e.g., being the youngest child, since parents often learn from mistakes made on the first kids), and grew up to be the most grounded and "normal" of us three. The authors of Scared Sick continue: “Gestation is the time when our nervous systems are under construction and being wired for equanimity and stability or for hypersensitivity and vulnerability to the stressors of the world outside the womb--in other words, the time when we are primed for either vulnerability or relative durability in response to later trauma.” As Karr-Morse and Wiley note, mothers who are stressed have high levels of circulating cortisol, which can cross a compromised placenta, interfering with healthy fetal growth. High levels of cortisol also damage the developing baby's hippocampus, forcing a focus on survival instead of higher thinking and connecting with other people. So this might help explain why my sisters ended up with healthier responses to stress and no one ever accused them of excessive sensitivity as they did me. Jillian and Sia likely experienced a less cortisol-filled prenatal environment than I did, as June seems to have experienced less stress during their pregnancies. Thus I was exposed to elevated stress hormones that have the power to wire the brain differently. As science now demonstrates, this likely contributed to my social anxiety and perpetual struggles with school and work. But by far the most humiliating manifestation of this maladapted wiring occurred in my direct interactions with people when--as we learned in my last post--my neuroception detected threat. It was precisely in those moments, when I was on the spot or learned that I was displeasing June, that I could feel my brain shut down even as I tried to rally it (which only generated a shame spiral as June would grow even angrier with me in my frozen-brain state). I routinely failed under pressure in all performance-type situations like piano and viola recitals and public speaking, when I would trip up or even stop cold as a crippling fear overtook me. It turns out it wasn’t just a matter of choosing not to "think," as June accused me of doing. There was a physiological basis for this behavior grounded in early trauma. It’s in the neural pathways that an individual develops in response to overwhelming stress, as a survival mechanism that falls closer to the freeze response along the fight-flight-freeze spectrum, as I detailed in my last blog post. Scared Sick reports on studies finding that babies of mothers stressed during their pregnancies are twice as likely to experience behavioral problems, anxiety, and depression as children, an inability to cope well with new people and situations, and ADHD. Check, check, and check, for me: I was put on Prozac in its earliest days on the market shortly after I was shipped off to boarding school, and Lexapro and Adderall later as an adult suffering chronic depression and social anxiety who could barely focus at work. The Additional Trauma of Premature Birth Growing up in our family, the fact that I was born several weeks premature with near fatality was just another fact of no consequence, like the fact that I have brown eyes. But well after my childhood was over, interesting new information came out from the medical and psychology fields concluding that pre-term birth actually is a bigger deal than we thought; it presents significant stressors and resulting developmental challenges with enduring effects. What I described earlier is just the prenatal, gestational sources of trauma. It's not a stretch to see how these unhealthful conditions can lead to premature birth (among other problems), as the authors of Scared Sick confirm. But escaping a stressful womb provides the new baby with little relief. For pre-term infants like me, who likely were born early due to stressful gestation and thus are already compromised, it's out of the frying pan, into the fire as they face a whole new set of stressors during their stay in a preemie ward, or neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). The NICU provides a notoriously uncomfortable and agitating environment for vulnerable pre-term infants, with bright lights and loud noises (including low-frequency sounds that as Dr. Porges points out our ancient nervous systems associate with vocalizations of predators). A preemie's delicate skin still needs the warm, wet environment of the womb but is instead exposed to rough textures. These young patients are also hooked up to medical equipment and most of the human contact they receive involves the administration of multiple painful medical procedures a day instead of the loving touch they need. Babies are never too young to feel, store memories of, and have their nervous systems detrimentally programmed by pain. Carr-Morse and Wiley report pain specialist Anna Tadio’s findings on the long-term effects of painful procedures on babies: When we do something to a baby that is not an expected part of its normal development, especially at a very early stage, we may actually change the way the nervous system is wired. This is precisely what many leading researchers now believe sets the stage for later disease, both physical and emotional. We are inadvertently altering the nervous systems of young human beings--almost always unknowingly and for good, often life-saving reasons--but there are consequences in later development which are typically disconnected from their roots in earliest experience and are often misdiagnosed. This is confirmed by Dr. Stephen Porges, who developed the Polyvagal Theory and observes in his book I referenced in the last post: "We often forget that medical procedures may convey cues to our body that are similar to physical abuse. We need to be very careful about how people are treated. Even interventions administered with positive intentions that may involve restraint may trigger trauma responses and even PTSD." A study published in the Journal of Perinatology in 2003 sums up findings of the effects of stress and trauma on preemies in the NICU (I’m including their entire summary here, which, I know, is a crappily excessive quote--but this blog post I’m writing is no research paper and I’m providing full attribution and not claiming it as my own, so...): For many years, conventional wisdom declared that infants and small children could not cognitively remember chronic stress or trauma. As a result, professionals assumed that children would not experience long-term problems from traumatic incidents that occurred before their cognitive memory was functioning (around the age of 3). In the past decade, researchers have made tremendous strides in negating this belief based on their improved understanding of the long-term physiological impact that chronic stress, as well as traumatic incidents, have on the developing brain. The brain triples in size over the first 5 years of life. Much of this growth is in the myelination of neurons and their synaptic interconnections. Genetics determine the basic architecture of the brain, but its final form is dictated by experiences in the environment. If an infant's or child's experiences are abnormal, non-nurturing, traumatic, and/or chronically stressful during a time of immense change in the development of the brain, then this impact may leave a permanent imprint on the structure and mechanisms of the functioning brain throughout life. The stress response system is activated by a centrally located area in the right hemisphere of the brain, the area of the brain that is dominant in controlling the functions that are used for survival, processing bodily information, reception and regulation of emotion, and the regulation of affect. In the early development of the brain (postnatally), the right hemisphere is also more deeply interconnected (than the left hemisphere) with the limbic, autonomic, and arousal systems, all areas of the brain that are important in the modulation of stress. When an infant encounters stress, these areas of the brain are primary in telling the body how to respond, that is, when and what hormones to release (corticosteroids, vasopressin, oxytocin, etc.), when to increase the heart rate, how to mobilize energy, etc. When the threat has passed, the same regions of the brain communicate, via the same or similar neurons and neurotransmitters, when and how to return to baseline. We have known for many years the importance of, and how the brain responds in acute stress. Just in the last decade, however, researchers have found that chronic stress or trauma (especially when it occurs while the brain is developing) can have detrimental results both psychologically and biologically. As the brain is developing structurally and mapping its neuropathways, these pathways are frequently compelled to take abnormal directions in order to deal with constant stress and/or trauma (such as those in the NICU and/or after discharge), which in turn can cause brain function to become abnormally integrated. When discussing an infant's or child's response to trauma, Perry et al. explains, “in the developing brain, these states [temporary responses] organize neural systems, resulting in traits. Because the brain changes in a use-dependent fashion and organizes during development in response to experience, the specific pattern of neuronal activation associated with the acute responses to trauma are those which are likely to be internalized. The human brain exists in its mature form only as a byproduct of genetic potential and environmental history”. Streech-Fischer and van der Kolk believe that “chronic childhood trauma interferes with the capacity to integrate sensory, emotional and cognitive information into a cohesive whole and sets the stage for unfocused and irrelevant responses to subsequent stress." Theoretically, as a premature infant grows, he/she may not be able to distinguish, on a subconscious level, between the here and now of a stressful event and the past events of the NICU due to the atypical development of his/her brain. In addition, if a premature infant's brain is programmed to respond to constant stress, subsequently as he grows older, he may have a difficult time sorting out how to respond normally to everyday circumstances. It is important for us to abandon the myth that infants and children can “get over it because they didn't even know what was happening.” Dr. Perry et al. believes that “children are not resilient, children are malleable”. We must recognize the potential effect from the difficult events in the lives of premature infants and children. Wow. I can’t tell you how much this meant to me when I read it. After years of others shaming me for my routine brain shut-down and heightened sensitivity, I now had science on my side explaining the source of these problems. In your average NICU, the driving imperatives are efficiency and mere survival over holistic care for long-term thriving. So, metaphorically speaking, there are no cradles in a preemie ward--and no hands to rock them. But this has repercussions for the babies' development. The authors of Scared Sick explain the origin of the fight-flight-freeze response that eventually manifests in their lives: [I]f no one responds to the baby’s cries and she is left to fend for herself, or if she is abused or exposed to violence by the hands that should be there to rock the cradle, her lower brain will be highly stimulated. Because the brain builds itself from experience, this kind of stimulation, if it occurs chronically, will build an overactive or highly sensitized response system in this little brain. Now one of two things will take place, depending on the child’s age, circumstances, and temperament. She may remain in a state of hyper-arousal, crying and flailing about. Or, overwhelmed by terror, she may, like an electrical circuit receiving too strong a current, simply switch off--she freezes and dissociates. In extreme cases, she may faint. For many children, this is the beginning of “learned helplessness”--going directly into passive defeat in the face of threat rather than putting up a fight. This. This likely explains how my experience as a preemie caused my nervous system to default to the freeze or immobilization response--a dysfunctional orientation that would haunt every aspect of my life for decades to follow, from relationships to learning to will/drive to self image. And then what happened after I left the incubator and went home? Well, I already covered that in my origin story a few blog posts back, where I explained how an abusive environment ensured that I never really felt at home, at home. Really, my life has involved jumping among an endless series of frying pans and fires. (It turns out this was cosmically orchestrated for some very good reasons that I'm unfolding on this blog. There truly is a reason for everything.) A New (Ancient) Way To Care for Preemies: More Human Contact Some within the neonatal healthcare system are starting to recognize the trauma preemies face and to minimize it through "family nurture intervention" (the successor to "kangaroo care") which involves parents traveling to the NICU daily if possible and holding their preemies on their bodies and speaking to them, since skin-to-skin contact with an emotionally regulated adult provides crucial co-regulation for the baby's developing autonomic nervous system. This helps not only babies but parents, too--in developing a stronger emotional connection to their children. Below is a two-part PBS NewsHour series on the subject. The major takeaway from my blog posts in this series thus far? To be truly healthy in life and prevent family stress leading to maternal burn-out and various forms of child neglect and abuse, we need more than just one hand to rock that cradle--and it needs to start before the baby even arrives. That's the subject of my next "Systems Busting" blog post. But first, something a little different.... Comments are closed.

|

Archives

May 2022

Categories |