I believe that authenticity matters; hiding who we are stifles growth opportunities for the individual and collective. So in this blog I write about all things that genuinely fascinate me: art, spirituality, the puzzles of personhood--and their ongoing interplay. For some, learning the artist's thoughts contaminates the experience of the art, and I respect that. It might be best to avoid this blog and visit only my gallery pages. Personally I can't get enough of the stories, ideas, and people behind art, so this blog is most appropriate for an audience similarly curious and open-minded, and who won't take offense at challenging perspectives and taboo topics. It's especially for those who are aware they're undergoing a spiritual awakening and seek to feel less alone in that process. I wouldn't be at this better place in my life if it weren't for the wayshowers I found online who helped me understand what was happening to me and to the world, and I hope to pay it forward by doing the same for others on the awakening path.

|

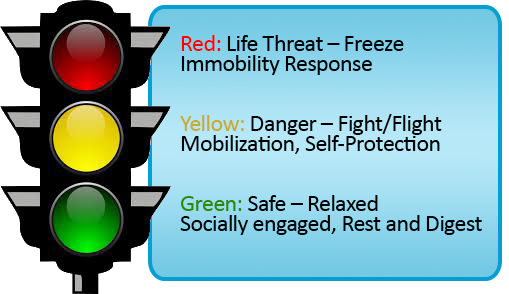

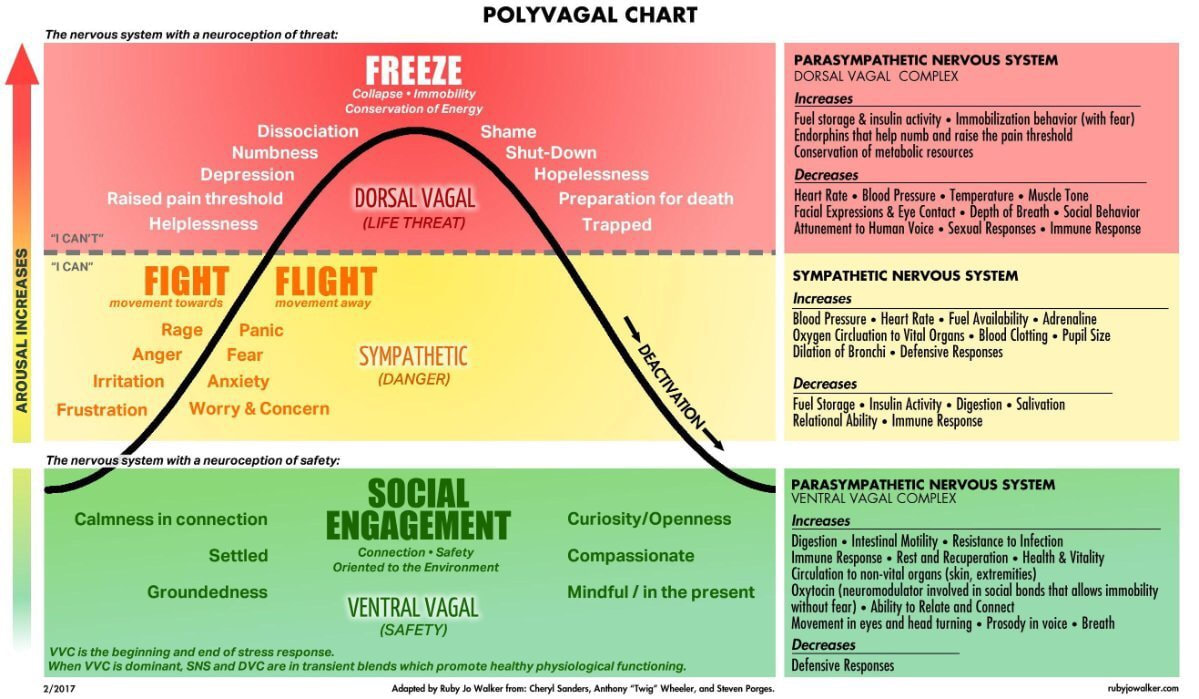

This is the third in a series of posts on what I've learned from my dysfunctional upbringing and my thoughts on how the systems and beliefs that comprise our culture can improve. For my full story, see the December 2020 post titled, "We Are Shaped by Our Experiences: An Origin Story Pulled from the Shadows." My intention is to inspire others to develop greater awareness about their own lives and to share ideas for building healthier, more supportive families and communities. Because I believe, as Teal Swan says, "We are given the very wounds we are meant to teach others to heal." In the last post I introduced what could be an uncomfortable and/or liberating new idea for many: that trauma is more than we think. It’s big stuff (wars, natural disasters)--but also little stuff that we’re not used to thinking of as detrimental. In this post I discuss the groundbreaking theory that identifies an important physiological missing link between our experiences and our emotions and behaviors that follow them. The Autonomic Nervous System and the Roles of the Vagus in It The autonomic nervous system controls and regulates internal organs and glands. Its operation is autonomous or automatic, that is, not requiring conscious effort. The vagus is the largest nerve complex in the autonomic nervous system and is most often associated with an ability to calm us down. The medical community has long presented the autonomic nervous system in an oversimplified way, that it comprises 1) the sympathetic nervous system that prepares the body to mobilize in response to danger with the fight/flight defense, and 2) the parasympathetic nervous system that restores the body to a calm state so it can focus on its everyday maintenance functions (think "rest and digest"). Conventional thinking said that these two systems oppose and balance each other, and that it was best to be more “parasympathetic” or “vagal”--i.e., more calm. But as medical researcher Stephen Porges learned, the vagus in mammals can cause death by slowing the heart rate to dangerous levels and stopping breathing. This paradox of the vagus--that it could calm or kill, depending on how much it slows the heart rate and other vitals--intrigued Porges, whose investigation of it eventually led to his development of the Polyvagal Theory. (This blog post draws mainly from a compilation of Porges's interviews on his theory for the layperson: The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory.) Porges emphasizes that in humans and other mammals the autonomic nervous system actually comprises three distinct subsystems, instead of two: 1) vagal pathways that regulate the organs above the diaphragm, known as ventral vagal, 2) vagal pathways that regulate the organs below the diaphragm, or dorsal vagal, and 3) the sympathetic nervous system. Each of these three subsystems emerged at a different point in the evolutionary history of vertebrates. The dorsal vagal system was the first to develop (thus most ancient) and is shared across all vertebrates. It causes the organism to immobilize, or freeze, in the face of threat. The second nervous system to develop was the sympathetic, which activates the fight/flight defense when endangered. The third and newest system, the ventral vagal, emerged with mammals--including humans--which require this specialized branch due to their unique needs for social interaction crucial for development, health, and safety. Let’s take a closer look at these three subsystems. Ancient Vagal Pathway The ancient vagal system shuts down social behavior, slows heart rate, inhibits breathing, and halts many other normal bodily functions when faced with threat. Think of a mouse caught in the jaws of a cat, which will appear dead even though it isn’t. Immobilization might look like the animal is giving up, but it serves a defensive purpose: By slowing and even stopping certain bodily functions it is protecting the trapped animal from feeling pain and keeping it from further moving, which might provoke greater injury by the predator. When an animal experiences conditions of safety, this same ancient vagal system supports health, growth, and restoration. Sympathetic Nervous System As vertebrates continued to evolve, the sympathetic nervous system appeared, first in bony fish. When detecting danger it causes release of stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol, speeding the heart rate, sending blood to large muscles, redirecting energy away from digestion--thus enabling defense through mobilization. The newer sympathetic defense inhibits the older immobilization one. Mammalian Vagal Pathway for Social Engagement When mammals evolved onto the scene, in them emerged a new, specialized vagal pathway that inhibits the sympathetic nervous system response by promoting social engagement behavior. Why is this important? Mammals are uniquely relationally dependent creatures; their survival and development depend on social relationships. While reptiles and fish generally do not care for their young after they're born, young mammals require a great deal of care at this early stage in life, including nursing--a highly social way to receive nourishment. Mammals also must cooperate socially to play, protect the group, and often to obtain food. It is vital that they know when to lower (downregulate) their defenses in order to meet their mutual needs through social engagement. The new mammalian vagal system uses social interaction to downregulate the defenses of the older circuits. The way this social engagement system works is through the ventral vagus complex whose nerves are connected to the muscles of the face and head. These muscles control functions involved with social communication, like the abilities to vocalize using high-pitched/friendly sounds or low/menacing sounds, to detect those same sounds with the ears, and to indicate intention (I want to hang out! I want you to go away!) through facial expression. Have you ever noticed how a lizard's expression never changes but a dog's certainly does, depending on how happy/defensive/sad it's feeling? That's the difference having a social engagement vagal complex will make. Social engagement is crucial to good health. As Porges explains, "When we are social and are engaged, we are reducing metabolic demands to facilitate health, growth, and restoration." Mammals retained the ancient vagal circuit even as they developed the sympathetic nervous system and later their newer vagal circuit. Fight/flight behavior became their primary defense strategy and they minimized use of freeze. Why? Because this most ancient defense response can kill them. Immobilization worked well in earlier-evolved, less complex animals like reptiles whose brains are smaller. They can tolerate reduced blood flow to the brain and go without breathing for an extended period of time and still live. But since mammals’ larger brains require more oxygen, slowing or stopping breathing can be lethal. So under what circumstances is immobilization still triggered in mammals? Here it is helpful to show the traffic light visual that Porges uses to depict how a mammal (including human) responds to the three major levels of threat in its environment. When we feel safe, i.e., an absence of danger or threat, our ventral vagal system engages, greenlighting relaxed, prosocial behavior and bodily focus on good health. When sensing danger that we feel we can handle effectively by either fighting or fleeing, this recruits our sympathetic nervous system to mobilize, subjugating health to safety. When we sense a more severe threat, one that can end our lives, that’s when the immobilization reflex occurs, also prioritizing survival over optimal health. Neuroception A key point here is that determining what constitutes a threat in its environment is not a conscious decision for an animal--or for a human. Porges coined the term neuroception to describe the nervous system’s automatic evaluation of risk in the environment. We're all familiar with perception, an example of which is seeing an animal and objectively identifying it as a large, furry, striped tiger staring at you with yellow eyes, crouching low about 30 feet ahead. An example of neuroception is seeing that same animal and instantly feeling fear and the desire to escape as your heart beats faster, breathing shortens, muscles tense, and skin starts to perspire. Perception requires conscious thought. Neuroception doesn’t. Below is a more elaborate diagram summarizing how human neuroception determines and responds to different levels of threat (click on image to expand for easier reading). Notice how this diagram also indicates human emotional and behavioral states, with words like “joy and compassion” associated with the condition of safety and social engagement, “fear” and “anger” for a state of fight or flight, and “depression” and “shame” for the freeze state. This is a crucial point: our emotional states and behaviors stem directly from how safe we feel and whether and how our nervous systems detect threat in our environment. How Polyvagal Theory Explains Persistent, Dysfunctional Behavior Born of Trauma Polyvagal Theory shows how we automatically recruit different subsystems of the autonomic nervous system, depending on our needs to handle different levels of threat and socially engage for optimal health, and that these subsystems work together to ensure that we maintain a state of normal functioning as much as possible. But as I read Porges's book a question nagged me: What if one's normal state is to be abnormal, as in my case and that of many others? Can this theory explain why people like me continue to display disproportionate responses to everyday stressors that most others could handle well? Can one's neuroception be wrong? Porges first introduced Polyvagal Theory in 1994 in his presidential address to the Society for Psychophysiological Research. The theory has had a major impact on the scientific research community and has been cited in thousands of peer reviewed publications across many disciplines. His intended audience was scientific researchers, but to his surprise his model soon was embraced by clinicians treating people with histories of trauma whose bodies, says Porges, "were retuned in response to life threat and lost the resilience to return to a state of safety." Porges initially had no interest in trauma treatment. But he credits Drs. Peter Levine, Bessel van der Kolk, and Pat Ogden with showing him how his theory applies to understanding and rehabilitating those with trauma. Deeper into his book Porges does address my questions about neuroception that might be off. "Sometimes we are not prepared for these adaptive reactions and the reaction is a surprise--for example...feeling dizzy when reprimanded...." Whoa--remember from my story when I would get light-headed and nauseated when experiencing my mom's wrath? Now I know why: for some reason my body interpreted such circumstances as a threat to my life. As Porges says, "We are also vulnerable to faulty neuroception, when the nervous system detects risk when there [is] no risk." Porges explains the traumatic origins of this phenomenon: In some cases, the behavioral pattern and neural regulation of autonomic state changes drastically following trauma. These changes can be so great that the behavioral features may appear to represent a totally different person who no longer can relate to others or interact in the same world. Since the behaviors of the traumatized individual do not conform to the expectations of typical social interactions, the traumatized individual often feels that they are inadequate or cannot do things correctly. Wow. When I read this paragraph I felt like it was describing me. As I wrote in my origin story, I often felt unable to engage socially, like I never fit in anywhere, and that I was inadequate and incapable. Maybe because my trauma happened so early in life, it's not so much that I changed to become "a totally different person" following trauma (as Porges notes can happen) but rather that my guarded, introverted personality developed in response to a complex of traumas I experienced since (and even before) I was born. Who would I have been if raised under kinder, more healthful and relaxed conditions? Someone rather different, I feel confident to say. (Yes, I have a blog post coming on what I suspect is really up with introversion....) What Porges says about immobilization caught my attention because it zeroed in on my own case. He notes that a common faulty assumption in traditional therapy is that trauma activates only the fight/flight defense response in humans. ("Fight" was clearly my mom June's default defense.) But trauma can also activate the freeze defense. He says: "These clients are experiencing not a hyperarousal with increased mobilization behaviors but something more like a total behavioral shutdown coupled with subjective experiences of despair and even features of dissociation that may reflect a motivation to disappear." Again, wow--that sounds like me, and the emotional states of depression and suicidal impulse that haunted me for decades. In my thirties I started to feel guilty that as a child and teen I hadn't stood up for myself but caved to June's abuse when, in the moment, I would experience a highly physical helplessness that nearly caused me to faint. But Porges reassures those who respond with immobilization and dissociation: I try to explain to trauma survivors what their body has done. There seems to be a prevalent implicit feeling for many survivors of trauma that their body has done something wrong, something very bad. They need to be informed that their bodily response strategies may have been protective and saved their lives. Their bodily responses may have enabled them by immobilizing and dissociating to minimize physical injury and painful suffering by not fighting back. The immobilization may be very adaptive, since it may not trigger additional aggression. But it's odd that my body interpreted a parent yelling me as something lethal. So what could have happened to me that made my neuroception jump into the red zone of life threat, instead of fight/flight like most people (including June)? I explore the likely answer in my next blog post. (Here's a hint: we have to go waaaay back in my life....). But whatever happened in my life to cause this, Porges explains that the immobilization defense presents a unique challenge: "If a life-threatening event triggers a biobehavioral response that puts a human into this state of immobilization, it may be very difficult to reorganize to become 'normal' again. This is the case for many survivors of trauma." And, Porges notes, the type of animal we trauma survivors are matters: "Mammals evolved to be able to shift efficiently between safe/social engagement state and mobilization--but not between shutdown and mobilization or social engagement; there just is no efficient pathway out of it. Many people are in therapy because they can't get out of the immobilization circuit." Bells went off in my head when I read these words. So here’s why I’ve never felt normal or like I never fit in anywhere, why I lacked resilience, why everything--from learning to speaking coherently to social interaction--was way more difficult for me than for other people. My nervous system dwelled in freeze. It makes sense, doesn't it, that if someone can become stuck in a threat-responsive state due to trauma that permanently altered their nervous system, normal daily cognitive and social tasks would become more difficult for them since the body constantly prioritizes safety over cognition and social engagement. Says Porges: I think, in focusing on brain structures and brain functions in the way that has been done, we miss one of the major points...and that is the importance of bodily feelings and how they regulate and often subjugate our ability to access higher brain processes, including the higher psychological processes involved in thinking, loving, and socially interacting. I struggled with learning, and, although she tried to deny and hide it, so did June. This explains why. Notes Porges: "If we are not safe, we are chronically in a state of evaluation and defensiveness." If you read my origin story you'll remember how unusually defensive, fearful, and suspicious of others June was (e.g., when she grew paranoid about my shy friend Dahlia on my 12th birthday), how unloving and abusive she could be at times. Clearly her nervous system was programmed to detect threat more than normal. Something happened to her (and to me) when we were young and vulnerable enough that permanently adapted our nervous systems for more threatening environments. Hurt people hurt people. The Spiritual Dimensions of Polyvagal Theory Porges (joined by certain trauma researchers and clinicians like Bessel van der Kolk, Peter Levine, and Gabor Mate), embodies a more wise and empathetic perspective on trauma than most people are willing to, when he says: With trauma, it's not the event; it's the response to the event that is critical. To remind me I use the following phrase: 'everyone's hell is their own.' To me, this means that my judgments of the traumatic event are irrelevant to the client, and it is the client's response that determines the trajectory of the outcome. Therefore, for situations that we may think are relatively benign, another individual's nervous system could respond to it as if it were a life-or-death situation.... The critical point is that we must respect that our nervous system sometimes may functionally betray our intentions while attempting to save us. You know what I thought of when I read that last passage? A saying that I see floating around spiritually-aware social media from time to time: Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a battle you know nothing about. Is it ironic that Porges arrived at his compassionate-sounding perspective through the cold logic of his scientific research? Not to me--because it's just one more example in a recent trend I've noticed: the convergence of science and spirituality (another blog post on that coming up). Science-based Polyvagal Theory tells us that people need people, and that what boils down to the kindness or unkindness of those interactions greatly influences a person's mental, emotional, and physical well-being. And what is the common message undergirding nearly every religious and spiritual tradition (in its purest form, anyway)? Be kind. I'd like to think we don't really need the Polyvagal Theory to tell us how to behave toward one another. But in these times when so many have become so far removed from their basic humanity, maybe we do. In that case, it's good to know that for those who need such proof, the imperative for kindness can be backed up with cutting-edge science. Here is another of Porges's conclusions that echoes a foundation of new-age spiritual teachings: that our civilization has focused too heavily on thinking and the brain, at the expense of feeling and the body's own unique forms of intelligence--and that it's time to restore balance between the two. As Porges points out, Western culture prioritizes thoughts over feelings, pithily encapsulated in Descartes's philosophical statement, "I think, therefore I am." Porges muses on "how our treatment of people would have evolved" if Descartes instead had said, "I feel, therefore I am": Where would we be today in terms of a historical trajectory of what it is to be a human? Instead, based on Descartes, our culturally based philosophies have adopted the premise that to be a good human, we have to depress or reject our visceral feelings to enable our good brain, our smart brain, to express its potential. Physical and mental illness may be a consequence of an adherence to Descartes's dictum. Thus, not respecting the body's own responses and filtering visceral feelings, over time, may contribute to illness by dampening the bidirectional neural feedback between brain and body. Reading this jerked me back to my childhood and the relentless efforts of authority figures, chiefly my mom, steering me away from my feelings, condemning me for my emotional sensitivity, and demanding, "Come on, Jenny, think!" This only cut me off from an important, alternative source of intelligence: my own body--with devastating consequences for my physical, emotional, and mental well-being. Here's another way in which Porges unwittingly aligns with a concept common in new-age spirituality (which recognizes that humanity and Earth are currently ascending from the polarity and duality of the third dimension [right/wrong, good/bad, negative/positive] to the fifth dimension where such divisions are obsolete): that to understand and truly help people we must abandon dualistic thinking based on moral judgments, and recognize that everything in our realities has served our experience in some way. Says Porges: I use the term 'moral veneer' as the feature in our society that pushes us to evaluate behavior as good or bad and not to see the adaptive function of the behavior as regulating physiological and behavioral state. A few pages later: I do not like to conceptualize behaviors as good or bad but view each behavior as sitting on a neural platform that represents the organism's attempt to adaptively survive. However, although this model enables behaviors to be conceptualized as adaptive, some behaviors interfere with appropriate social behavior and social interactions. Thus a goal of therapy would be to enable clients to regulate their visceral state and to engage and to enjoy interactions with others. Of course, one of the most important spiritual tenets is that we ultimately are all one; we come from the same source, and it is back to this same source we are now returning as we enter the upswing of a grand cosmic cycle following our long, dark experience in separation that was necessary for our collective evolution. Science like this serves us well on this journey when it asks us to validate and understand the experiences of others, which can only bring us closer together. What Polyvagal Theory Means for Individuals, Families, and Communities Porges lays out the social implications--the beating red heart--of Polyvagal Theory: So the real issue in understanding the Polyvagal Theory is to realize that humans, being mammals, need other mammals, other humans, to interact with to survive. The important aspect is really the ability to reciprocally interact, to reciprocally regulate each other's physiological state, and basically create relationships to enable individuals to feel safe. If we see this as a theme through all aspects of human development and even aging, then concepts like attachment start to make sense, as do concepts like intimacy, love, and friendship. But then again, concepts like bullying and having problems with individuals or spousal conflict also start to make sense. Oppositional behavior in the classroom starts making sense. Basically, our nervous system craves reciprocal interaction to enable state regulation to feel safe. And disruptions to this ability to have reciprocal interactions become a feature of dysfunctional development." Now, that being said, people have thought that's behavioral, not physiological. But the Polyvagal Theory informs us that it is physiological, and that the neural pathways of social support and social behavior are shared with the neural pathways that support health, growth, and restoration. They are the same pathways. Mind-body and brain-body sciences are not correlative; they're the same thing from different perspectives." So, the bottom line is the understanding that the human nervous system, like all other mammalian species, is on a quest, and the quest is for safety, and we use others to help us feel safe. Here is my takeaway from Polyvagal Theory: People need people--our very physiological, mental, and emotional health depend on it. But the types of people around us and the quality of these relationships matter a great deal, since humans have enormous capacity both to help and hurt one another. The stories of how nurturing or damaging our relationships have been are written into how our bodies function; we truly are shaped by our experiences. This affects our behavior, which in large part determines the paths we take in life and how connected we are to others, which in turn affects how healthy we are and how our bodies function....in a spiraling biobehavioral cycle. (I was going to use the adjective "vicious," but that would be dualistically judgmental of me....) In the next blog post I explore the likely triggering event for my own chronic default to the immobilization defense, as well as other reasons behind my unusual inability to handle stress of any kind. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

May 2022

Categories |