I believe that authenticity matters; hiding who we are stifles growth opportunities for the individual and collective. So in this blog I write about all things that genuinely fascinate me: art, spirituality, the puzzles of personhood--and their ongoing interplay. For some, learning the artist's thoughts contaminates the experience of the art, and I respect that. It might be best to avoid this blog and visit only my gallery pages. Personally I can't get enough of the stories, ideas, and people behind art, so this blog is most appropriate for an audience similarly curious and open-minded, and who won't take offense at challenging perspectives and taboo topics. It's especially for those who are aware they're undergoing a spiritual awakening and seek to feel less alone in that process. I wouldn't be at this better place in my life if it weren't for the wayshowers I found online who helped me understand what was happening to me and to the world, and I hope to pay it forward by doing the same for others on the awakening path.

|

This is the second in a series of posts on what I've learned from my dysfunctional upbringing and my thoughts on how the systems and beliefs that comprise our culture can improve. For my full story, see the December 2020 post titled, "We Are Shaped by Our Experiences: An Origin Story Pulled from the Shadows." My intention is to inspire others to develop greater awareness about their own lives and to share ideas for building healthier, more supportive families and communities. Because I believe, as Teal Swan says, "We are given the very wounds we are meant to teach others to heal."

Quick: List five examples of trauma. Maybe picturing the trauma care center at your local hospital, you’ll likely name big, unforeseen events that cause severe bodily injury, like heart attacks, car accidents, gun crimes, and building fires. For much of our modern history, perhaps the least controversial definition of trauma is something like this: an acute, physical, often violent event that surprises and harms us in the moment that it occurs. Maybe your definition of trauma extends to events that seem to leave the body intact but shock the mind, like a soldier's experience witnessing the unbearable carnage of combat--events that are linked with an eventual cascade of behavioral problems that fall under the term post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. The federal government only fairly recently accepted PTSD as a legitimate problem among its veterans of war, as Dr. Bessel van der Kolk recounts in his 2014 book, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. But as the author asserts, "One does not have to be a combat soldier...to encounter trauma" with similar long-term effects. He goes on to list statistics associated with the famous ACEs study, described below, that identified sources of trauma in the home environments of the country's youngest--and thus most vulnerable--population.

ACEs

In the mid-1990s, a groundbreaking study by Kaiser Permanente and the CDC drew attention to the long-term effects of trauma occurring specifically in childhood. Researchers were interested in the possible links between a person's experience of certain types of childhood trauma and the condition of their health and psyche as adults. The study was prompted by findings in the 1980s that the majority of adult participants who dropped out of a particular obesity clinic’s weight loss program--despite successfully losing weight--had experienced sexual abuse as children. Researchers suspected that obesity might serve a purpose in the dropouts' lives by helping them cope with the psychic residue of that abuse in a twisted way. As they later discovered, gaining dangerous amounts of weight did indeed help former abuse victims to maintain a sense of safety by avoiding attracting potentially harmful contact--even though they initially desired to be lighter and healthier. The Kaiser study surveyed over 17,000 volunteers, asking them about their history with the following types of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, domestic abuse of the mother, substance abuse in the household, mental illness in the household, parental separation or divorce, and incarcerated household member. Subjects were also surveyed on their health and psychological conditions as adults. As the CDC summarizes the study’s findings, ACEs are common across all populations, social and economic conditions put certain populations at higher risk for experiencing ACEs, and a greater number of ACEs a person has experienced increases the risk of negative impacts on their lives. These impacts include learning and behavioral problems in school, chronic depression, suicide attempts, alcoholism, IV drug use, unintended pregnancies, being the victim or perpetrator of violence later in life, and a greater chance of suffering from severe health conditions like heart disease, liver disease, emphysema, and cancer. The ACEs study scientifically validated for the first time a wide variety of stressful childhood circumstances as the trauma underlying the country's largest public health crisis. Developmental Traumas In The Body Keeps the Score, van der Kolk's definition of trauma seems to hew to the definitions I've presented thus far: acute, physically violent events and the ACEs categories. While he acknowledges that "[t]rauma affects not only those who are directly exposed to it, but also those around them," he stops short of describing as trauma the experiences of those who have to live with traumatized people on a daily basis, e.g., the depressed spouse of a former soldier with PTSD or the anxious children of a perpetually angry parent who grew up with an alcoholic father. But because #evolution, now there is growing recognition of this very class of traumas, particularly for its prevalence in childhood. Lissa Rankin, M.D., who has been researching trauma for a book she’s writing, provided an update on her findings in a Facebook post a couple years ago: “I think what's important to remember is that situational trauma- sexual abuse, wars, criminal violence, household substance abuse, in other words the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE's)- are not the only kind of trauma. Developmental traumas, like growing up with a controlling parent, are just as traumatizing and more insidious [emphasis added].” Dr. Rankin herself had personal experience with parental control, which she detailed in her newsletter after she had been able to process her mother’s death. Even though her admittedly idyllic childhood was filled with many examples of parental love and care, she also could recall her mom’s controlling behavior that decades later still sent Rankin seeking various forms of therapy for its persistent effects on her psyche and behavior. This is significant for a former OBGYN surgeon who, like all conventional medical professionals, was trained to toughen up mentally and desensitize herself. I know why Rankin uses the word “insidious” to describe developmental traumas: because our society has long denied various forms of abuse that victims (which includes most of us at one time or another) were gaslighted into believing either weren’t happening or didn’t matter. I certainly experienced this. Well into my adulthood, my mom would dismiss my lingering distress over childhood memories with invalidating one-liners like, “Your life was not a Dickens novel!” or, “If you want to see a dysfunctional family watch The Forsyte Saga!” Developmental trauma is so damaging precisely because it wreaks havoc in a society that refuses to acknowledge it, with shame as its biggest accomplice and silencer. As my ex-boyfriend crudely scolded when I admitted how much the emotional abuse I endured as a child still bothered me in my early 30s, “At least you weren’t f***** up the a** by an uncle!” (Bullies, aka people who haven’t allowed themselves to feel the pain of acknowledging and integrating their own trauma so they unconsciously attack those who represent the vulnerability they themselves can't bear to show, are perfectly positioned by the universe in your life to test your ability to know and trust yourself. He was one of them and I can’t wait to get to his story. In hindsight the signs were everywhere that he was deeply affected by his own dysfunctional family life and excessive parental control and barely realized it.) Rankin is just one in a wave of new thought leaders asking us to look beyond the incomplete diagnoses (it’s just a random disease or chemical imbalance) and inadequate therapies (slice ‘em up or fill ‘em with pills) of the medical and psychological communities that target only the symptoms of much deeper problems. Canadian physician Dr. Gabor Maté is one of the leading pioneers and experts linking childhood traumas and other forms of stress with disease, behavioral problems, and addiction. His 2003 book, When the Body Says No: Exploring the Stress-Disease Connection, plumbs his own patients’ histories and those of well-known public figures for the stressful precursors to their eventual health problems. Maté bolsters these connections with an astonishing array of scientific evidence, detailing the biological mechanisms linking suppressed emotions with bodily disturbance. For example, the experiences of Maté’s own multiple sclerosis (MS) patients and the experiences of others described in the MS literature share the common ground of acute and chronic stress during childhood conditioning that blocked their normal fight-or-flight response. Studies on lab rats confirm that blocking the fight-or-flight response worsens MS. Maté makes the powerful case that ignoring our instincts to eliminate or resist unhealthy stressors in our lives can have devastating physical consequences, including heart disease, gastrointestinal disorders, autoimmune conditions, and cancer. Interestingly, these conditions often debilitate the body to the point where a person can no longer fulfil the martyr’s role they were playing in their relationships. The body says no to social circumstances that are not serving our highest good when the conscious mind lacks the awareness and courage to say no first. For those of us who developed poor boundaries and learned to appease others just to survive in our dysfunctional environments, our illnesses are trying to spare us from more of the same. I clearly remember the turning point in my life where I finally accepted the validity of developmental traumas. It happened a few years ago while watching author, former addict, and spiritual seeker Chris Grosso as he interviews Dr. Maté in an online video. Maté has researched the link between childhood trauma and addiction and asserts in his 2008 book on the subject, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: “[M]ost people who try most drugs never become addicted to them. And so, there must be a susceptibility there. And the susceptible people are the ones with these impaired brain circuits, and the impairment is caused by early adversity, rather than genetics.” When I first watched this video I hadn’t yet read Maté’s books so I didn’t know what I was in for. Although my own history continued to nag me, there was a part of me that still caved to popular opinion that I and others like me were just too sensitive. So I cringed as Grosso--white and middle-class but with a history of hardcore substance abuse--early on admitted that he had not experienced any of the “big” traumas as a child. I could feel myself concluding prematurely that he didn't really have good reason to become an addict...so this is going to be an awkward interview.... Boy was I wrong; instead it gave me an epiphany and the validation of my own feelings that I secretly had sought for years. Here is the relevant piece of dialogue where Maté turns the interview into a therapy session, asking Grosso some probing questions about his own life. At this point in the video Maté has just explained that addiction is never the primary problem; it’s only an attempt to find relief from emotional pain that typically has roots in intolerable childhood suffering. (Feel free to watch the first 11 minutes of the video directly below instead of reading the segment transcript that follows it.) Grosso: So that’s another aspect that I wanted to talk to you about, is the childhood element of addiction. A lot of people, when I did a...substance abuse counseling internship, many of the clients that I worked with came in and a vast majority of them had some sincere traumatic experiences in their life. Now you just mentioned that it doesn’t necessarily have to be a big event, because I look back at my own life and I am, you know, a hardcore addict, like to the bone when I was using, and my several years of relapse, full-on. But I look at my childhood, and relatively, in comparison, it was not bad. I love, I have a good…. Maté: Let me stop you right there, because that kind of thinking is precisely what prevents people from understanding their own life experience. So let me just look at, let’s say, let’s just look at your life if you’re willing to do that. G: I absolutely am willing to do that, yes. M: Ok, great. So tell me one thing that didn’t work for you in childhood that made you unhappy. Not in comparison to anybody else--just you. G: Umm… M: Do you know or do you not know? G: Yeah, the first memory that’s coming up for me is more teenage years, but not childhood. Um…. M: All right, let me ask you a question: Were you bullied as a child? G: I was not bullied, no. M: Ok, either of your parents drank at all? G: Nope. M: Did they hit each other? G: They did not hit each other. M: Did they yell at each other? G: They didn’t yell but they definitely fought, um, not a lot, but they did. M: Was either of them depressed or anxious? G: Um, not that I was aware of. M: I’m not asking whether you were aware as a child, I’m asking in retrospect. G: No...and no, honestly in retrospect, I don’t think so. M: Ok, so you really just cannot identify anything? Nobody ever sexually abused you? G: No, I did not have sexual abuse. What I can say, what I do know from my own experience, my parents were very young when they got married, um, I was the firstborn, so there was a big learning curve, so I’m sure that that impact me growing up. M: “It’s a learning curve,” what do you mean? G: Um...what I mean is...so, first-time parents, they were 21 when they had me, newly married, so my brother--I have one sibling two years younger--so by the time he was born they had a bit, at least a little experience, um…. M: Ok, but you’re not talking about your experience, like it sounds like you have a hard time tapping into an experience. G: Which I probably do, you’re right. I was just trying to share, what you were asking me about my, my parents, and I was just trying to give you something. Um, the only other thing I know is my dad was raised in foster care without his own father, without a father, so I know that was tough for him as well. M: Ok, so do you remember spending time with your father as a child? G: Yes, um, both my parents, yes, I did spend time with them. M: Were you ever sad or unhappy as a child as far as you can recall? G: Uh, yeah I remember being sad, I mean not what I would consider more than any other child, but I had periods of sadness. M: There you go comparing again. G: [laughs] M: Now, can you remember a period of sadness? How old can you go back to? G: Um...I think I have a lot of work to do here. I, uh…. M: Do you ever recollect being sad--I don’t care what age, teenagehood, before preteen, at any time…. G: Sure, well, teenage is very easy for me, ‘cause that’s where I started to really change a lot, but yes…. M: As a teenager? G: Yes, yeah. M: Who’d you speak to about it? G: Uh, I wouldn’t, really. M: You didn’t talk to anybody? G: No, that’s the thing, definitely not my parents, not really. Maybe, maybe some friends, but…. M: You have children yet, Chris? G: I have a stepdaughter. M: Ok. If your stepdaughter’s sad, who would you want her to speak to? G: She generally speaks with her mother, but she will speak to me... M: Yeah, you want her to speak to her mother or maybe to yourself, right? G: Oh, I would love for her to, yes. M: That’s what you would want is to speak to the parents, right? G: Yes, yeah. M: If your stepdaughter was sad and she didn’t talk to either of her parents, neither you nor her mother, how would you understand that? G: Right, you wouldn’t. M: As a parent, how would you explain it? It happened, she’s not talking to you, it happened. G: There’s some kind of disconnect, maybe a trust, maybe comfort…. M: How does it feel for a child not to be connected to their parents? G: Um...wow, not good. M: That’s how it doesn’t feel. How does it feel? G: How does it feel, uh....lonely, scary. M: Ok. You just told me about your childhood. By the time you were a teenager you learned that your parents weren’t available for you--and you learned that much before then, as a matter of fact. Now, here’s my question to you: If a six-year-old or a five-year-old such as your daughter says, “When I’m sad and lonely, I got nobody to talk to.” Would you say to them, “Oh come on, it’s not so bad. Think of the kids who are being beaten or sexually abused or starved.” Is that what you would say to a five- or six-year-old? G: No. M: But that’s what you’re saying to yourself. When you say that “not like, not like others, it’s not so bad,” you’re simply dismissing your own experience, which is the disconnection from yourself. Disconnection, in other words, how you survived your childhood, Chris, is you disconnected from yourself--which is the very meaning of trauma, as defined by Peter Levine, who you just talked to: my colleague Peter Levine, a trauma expert. So listen: that’s what happens in trauma is a disconnect. And as soon as you start comparing your own experience with that of anybody else, and as soon as you say, “It wasn’t as bad,” that’s a sign of the disconnect. And that’s the problem you’re trying to solve through your addiction. It’s all the pain that you had nobody to talk to. Maybe sit for a moment and really let Maté’s words sink in. What he’s describing is a developmental trauma that ultimately led to Grosso’s substance abuse. Here are some questions for you about that segment of the interview:

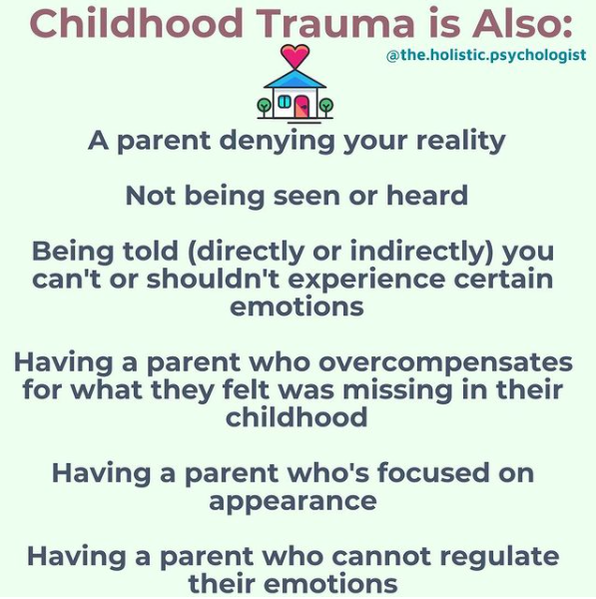

For so many of us in this culture who grew up with food, water, and shelter, but without anyone to confide in and around whom we felt accepted, understood, and maybe even safe and comfortable, we had a hard time putting our finger on what we were missing. They say you can’t miss what you never had. But Gabor Maté’s research confirms that our bodies and subconscious minds--which are other intelligent aspects of ourselves--do know what we’re missing and at some point will notify our conscious minds with physical symptoms we can't ignore. Just because the modern conditions in which we were raised were widely considered to be “normal” doesn’t mean that they were good for us or met our fundamental needs as the specific type of animal that we are. Like most other mammals we are fundamentally tribal creatures, which means that nurturing social connection is not just what we naturally crave, it’s imperative for our survival. (The biological basis for this is coming up in the next Systems Busting post.) The revolutionary perspectives on trauma first espoused by Drs. Gabor Maté, Stephen Porges, Bessel van der Kolk, and Peter Levine are pushing even further mainstream through a new generation of professionals sharing similar ideas in posts across social media. Dr. Nicole LePera, aka The Holistic Psychologist (who has amassed millions of followers), openly admits that much of what she learned in her graduate psychology training was of little use in helping her clients and herself. She posted this image on Instagram in November of 2020--and I was amazed at how perfectly it summarized my own childhood experience: The caption of the post reads (and ends on an optimistic note for those of us seeking to heal from what is finally gaining recognition as trauma): As a psychologist, I was trained to believe that trauma was a singular “big” event. Something that involved severe abuse or neglect. When I started my practice, I noticed a pattern with people who had ‘normal’ or ‘supportive’ families yet they struggled with severe anxiety or depression. Low self worth. Chronic fear of others think of them. Many were in toxic relationship patterns + had so much confusion around why they felt stuck. I noticed the same patterns in myself. Yet nothing ‘big’ happened to me. The next few years, I spent studying the patterns I saw + realized trauma is so much more than what we’ve been told. Trauma is an event where we are chronically denied our authentic nature as children, + are left to cope with our emotions without guidance in how to process them. This is where we learn to betray ourselves for love. This is where we learn that who we are is not acceptable + the ego comes in to create a sense of self based on the unconscious desires of a parent. We start to chase external approval because we’ve lost the connection to self. We seek relationships that mirror our earliest childhood experiences. If we had a parent who denied our reality (ex: an alcoholic father who we witnessed drinking + our mother, in denial herself, told us was just not feeling well) we have no trust in our own perception. We choose partners + situations where our reality continues to be denied. Unconsciously, we learned this as part of what relationships are. Our path to healing begins with an understanding that all of our behaviors, thoughts, patterns, + beliefs are simply our conditioning. They are not who we are. They’re a reflection of the past. Nothing is wrong with us. We are not damaged, or ‘mentally ill.’ As we become more conscious, we can make choices beyond our conditioning—in alignment with who we actually are. We are resilient humans who have learned how to cope. Humans who can now learn how to become empowered to thrive. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

May 2022

Categories |